In my earlier post I mentioned that Smoke was directed by Wayne Wang, but I didn’t say anything about the writer of the screenplay, Paul Auster. Without any disrespect to Wang’s direction, for me the main pleasure of this film is Auster’s contribution. I watched it as though Auster was entirely responsible for its authorship. In part, this is because, as I have indicated previously, I am entranced by the scope of Auster’s imagination and writing, however, the opening titles of Smoke encourage the privileging of the screenwriter over the director in this instance. It is a film by Wayne Wang and Paul Auster. In the closing titles, the film is ‘Written by Paul Auster’, adding weight to his authorship of the film, beyond that with which screenwriters are usually credited. I daresay that Auster’s well-established audience was a key consideration in the promotion of the film. The cameo appearance by Auster’s son, Daniel, as the ‘Book Thief’ is a signature that irrefutably marks the film as Auster’s, in a manner similar to Alfred Hitchcock’s on-screen presence throughout his oeuvre.

In my earlier post I mentioned that Smoke was directed by Wayne Wang, but I didn’t say anything about the writer of the screenplay, Paul Auster. Without any disrespect to Wang’s direction, for me the main pleasure of this film is Auster’s contribution. I watched it as though Auster was entirely responsible for its authorship. In part, this is because, as I have indicated previously, I am entranced by the scope of Auster’s imagination and writing, however, the opening titles of Smoke encourage the privileging of the screenwriter over the director in this instance. It is a film by Wayne Wang and Paul Auster. In the closing titles, the film is ‘Written by Paul Auster’, adding weight to his authorship of the film, beyond that with which screenwriters are usually credited. I daresay that Auster’s well-established audience was a key consideration in the promotion of the film. The cameo appearance by Auster’s son, Daniel, as the ‘Book Thief’ is a signature that irrefutably marks the film as Auster’s, in a manner similar to Alfred Hitchcock’s on-screen presence throughout his oeuvre.Watching Smoke this time, I was reminded of Auster’s most recent novel, The Brooklyn Follies. Both stories are set in Brooklyn which holds host to a range of isolated characters who are drawn into taking care of one another. There is something inexorable about the relationships that are formed, as if being responsible to those around them is intrinsic to the characters’ constitution. This is in spite of individual characters’ initial resistance to being more than considerate of the strangers they encounter. In Smoke, the character played by William Hurt is a writer named Paul Benjamin*. He buys cigars from a local tobacconist, Auggie (Harvey Keitel), and shields himself from others with the pain of his wife’s sudden death; she was shot, caught in cross-fire, on her way to work one morning. She was five months pregnant. Paul is drawn into the conversations which are part of the service in Auggie’s shop#. One evening, just as Auggie is closing up, Paul runs up to him, breathless, and asks him if he could still buy some cigars. Auggie raises the security grill on his door and soon Paul and Auggie are sitting at a kitchen table smoking, drinking beer, and looking through Auggie’s photo albums.

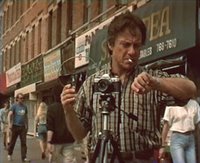

Auggie’s photo collection is a record of a ritual he has undertaken everyday for all the years he has owned the tobacco shop. Each morning at 8am, Auggie sets his camera on a tripod on the corner across from his store and takes a photo of the activity in ‘his’ corner of the world. He explains to Paul that it’s his project; his life’s work is represented in over 4000 photographs of the same corner in Brooklyn. Paul says that they’re ‘overwhelming’ and he flips through them rapidly, not really looking at them. At first, Paul doesn’t understand when Auggie tells him to slow down, after all the photos are all the same. Auggie explains how different each one is; because the earth rotates around the sun each day the light is slightly different in every one, to say nothing of the shifts in weather and thus the clothing people are wearing. Eventually Paul comes across a photo of his wife. He says, ‘Look at my sweet, sweet Ellen’.

Auggie’s photo collection is a record of a ritual he has undertaken everyday for all the years he has owned the tobacco shop. Each morning at 8am, Auggie sets his camera on a tripod on the corner across from his store and takes a photo of the activity in ‘his’ corner of the world. He explains to Paul that it’s his project; his life’s work is represented in over 4000 photographs of the same corner in Brooklyn. Paul says that they’re ‘overwhelming’ and he flips through them rapidly, not really looking at them. At first, Paul doesn’t understand when Auggie tells him to slow down, after all the photos are all the same. Auggie explains how different each one is; because the earth rotates around the sun each day the light is slightly different in every one, to say nothing of the shifts in weather and thus the clothing people are wearing. Eventually Paul comes across a photo of his wife. He says, ‘Look at my sweet, sweet Ellen’. The notion of a ‘life’s work’ is a recurring concern in Auster’s work. The nature of the obsessions that occupy the lives of Auster’s characters are often repetitive and seemingly pointless. As well as Auggie’s photographs in Smoke, there are the films made by Hector Mann in The Book of Illusions, which are produced without any desire on behalf of the film-maker that they will ever be shown, despite the interest in his work, which is exemplified by David Zimmer—also recently widowed—who devotes his time to ‘finding’ Mann. The endless walking of the streets of New York by Stillman in 'City of Glass' is incomprehensible to the character Quinn who decides to follow him on his apparently aimless meandering; and Quinn himself ends up spending his days waiting in all kinds of weather for a glimpse of Stillman after he has lost track of the older man. The point of the repetitive actions is, for me, best revealed in the opening sequence of another author’s work. In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera explains his understanding of Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return:

'...the idea of eternal return implies a perspective from which things appear other than as we know them: they appear without the mitigating circumstance of their transitory nature. This mitigating circumstance prevents us from coming to a verdict. For how can we condemn something that is ephemeral, in transit? In the sunset of dissolution everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia...

If every second of our lives recurs an infinite number of times, we are nailed to eternity as Jesus Christ was nailed to the cross. It is a terrifying prospect. In the world of eternal return the weight of unbearable responsibility lies heavy on every move we make. That is why Nietzsche call the ideas of eternal return the heaviest of burdens...' (4-5)

I’m not sure if my interpretation is entirely valid; I know that Auster references Cervantes’ Don Quixote a lot (especially through the characters who drop everything to follow their obsessions), but I don’t know enough about either Nietzsche or Don Quixote to know if the two are compatible. I suppose my referencing of Kundera’s work is premised on the notion that Auster’s characters are drawn to assume responsibility for one another through the repetitive obsessions in which they are engaged, or even just by taking time over the apparently tedious concerns of everyday life. It’s Auggie’s photographs that elicit a break in Paul’s numb façade, that enables him to finally grieve and thus to be comforted by Auggie. It’s the repeated appearances of the frightened young African-American boy who introduces himself variously as Rashid, Thomas and Paul (Harold Perrineau Jr.), who is on the run from some criminals he stole from, that prompts Paul to ask Auggie to give the teenager a job. Rashid uses the same method to get to know his biological father (Forrest Whittaker), sitting across the road from the garage he owns. It’s the drip, drip, drip of water from an overflowing bucket abandoned by Rashid onto Auggie’s stash of Cuban cigars that ends his dreams of making a fortune through trafficking the contraband. Rashid is able to reimburse Auggie the money he lost on the purchase of the cigars with the money he stole. Instead of reinvesting the money in cigars, Auggie now has the money he didn’t have to give to his ex-wife (Stockard Channing) who asked for his help with her daughter, and so he gives it to her without strings. It seems that through repetition the characters’ lives attain meaning, and they are unable to escape their responsibility to one another. The responsibility that the characters’ assume is not the ‘unbearable burden’ that Kundera first introduces us to—indeed he goes on to immediately question the negative attributes of weight—but it is a load that imbues the most apparently insignificant existences with ‘splendid’ life.

I’m not sure if my interpretation is entirely valid; I know that Auster references Cervantes’ Don Quixote a lot (especially through the characters who drop everything to follow their obsessions), but I don’t know enough about either Nietzsche or Don Quixote to know if the two are compatible. I suppose my referencing of Kundera’s work is premised on the notion that Auster’s characters are drawn to assume responsibility for one another through the repetitive obsessions in which they are engaged, or even just by taking time over the apparently tedious concerns of everyday life. It’s Auggie’s photographs that elicit a break in Paul’s numb façade, that enables him to finally grieve and thus to be comforted by Auggie. It’s the repeated appearances of the frightened young African-American boy who introduces himself variously as Rashid, Thomas and Paul (Harold Perrineau Jr.), who is on the run from some criminals he stole from, that prompts Paul to ask Auggie to give the teenager a job. Rashid uses the same method to get to know his biological father (Forrest Whittaker), sitting across the road from the garage he owns. It’s the drip, drip, drip of water from an overflowing bucket abandoned by Rashid onto Auggie’s stash of Cuban cigars that ends his dreams of making a fortune through trafficking the contraband. Rashid is able to reimburse Auggie the money he lost on the purchase of the cigars with the money he stole. Instead of reinvesting the money in cigars, Auggie now has the money he didn’t have to give to his ex-wife (Stockard Channing) who asked for his help with her daughter, and so he gives it to her without strings. It seems that through repetition the characters’ lives attain meaning, and they are unable to escape their responsibility to one another. The responsibility that the characters’ assume is not the ‘unbearable burden’ that Kundera first introduces us to—indeed he goes on to immediately question the negative attributes of weight—but it is a load that imbues the most apparently insignificant existences with ‘splendid’ life. *Names are carefully wrought in Auster’s work. They are always borrowed—from the author’s life, from the author’s other works, and from other writers’ lives and works—and each new borrower carries the full weight of everyone who has borne those names previously.

#One of the conversations that is not central to Paul’s story is one that occurs in the background between three of the shop’s regulars, one of whom is played by the vastly underrated Giancarlo Esposito—seen recently on television in 5ive Days to Midnight with Timothy Hutton. It prefigures another deftly placed conversation in The Brooklyn Follies about yet another war in Iraq.

2 comments:

I had a heap of links in this post, but Blogger doesn't seem to be co-operating at the moment. Everytime I put the links in--using the same process as always-- pieces of my post seem to randomly disappear. It's made me a bit cross. I'll add them later if I can be bothered.

One of the links you must have,however, irrespective of my mood,is a site on all things Paul Auster:

http://www.paulauster.co.uk/body.htm

This film was significant for me, but for what seems different reasons to yourself. Paul was the damaged, grieving, repressed man. Auggie was the hardened Brooklynite of dubious character. Even in the darkest of places, the bright spark of humanity can shine.

From a gender perspective, males are easily demonised or made to feel disenfranchised. It was, of course, through this perspective that I traced this post, after my post on Volver at Sarsparilla. Hardened males can be just as generous and gentle as anyone, though it may not be as immediately obvious.

Post a Comment