The difficulty began after I finished The Philosopher’s Doll by Amanda Lohrey. Instead of buying a new book, I decided to have another go at Atomised by Michel Houellebecq. Although an abandoned bookmark suggested I had read at least two thirds of the novel on my first attempt, I truly couldn’t remember anything about it, except perhaps a vague confusion about what was going on.

I decided to try Atomised again because I was reminded of it while trying to locate a link for The Philosopher’s Doll. During the search, I discovered that the Tasmanian State Library had nominated Lohrey’s work for this year’s IMPAC Dublin Literary Prize (I note it didn’t make the short list). I browsed the rest of the site and found that Atomised had won the Prize in 2002. I suppose I bought it because it won that award. In retrospect, I should have read the signs that warned me against any potential enjoyment of my rediscovery.

First of all, I didn’t like The Philosopher’s Doll. It’s divided into four parts with the first and second parts combining to make up at least three quarters of the book. Each of these parts are divided into chapters and are variously told from the perspectives of Kirsten, who wants to have a baby, and her husband, Lindsay, who doesn’t want to have a baby right now, and sets about purchasing a dog to offer his wife, with a view to stalling the demands of her biological clock. There’s nothing too wrong with the first two parts of the novel, they present both perspectives of a lived conundrum, and offer no easy answer. It’s when I began reading the third part that I wondered what the author was trying to achieve. All of a sudden, the perspective changes to that of a character who was barely been mentioned in the earlier parts of the novel. Sonia is a graduate student of Lindsay’s, and the impression conveyed by Lindsay’s voice, until the third part, is that she has been stalking him for a period, but she suddenly stops, leaving him a written apology before disappearing. When Sonia begins to speak, we learn that their relationship was more reciprocal than we had been led to believe. (Or maybe not?) So, the impression is that Lindsay was lying, which was not so much of a shock, considering his proposed solution to his wife’s desire for a child. But even if it was a revelation that had any kind of potential to demonstrate some deep insight into the human condition, the uneven structure of the novel completely undermined my sympathies for it as a story. As soon as I entered the third part, the book lost me. Emotionally, I was cast adrift.

The second clue that should have alerted me to avoid reading Atomised was the place of the aforementioned bookmark. Who abandons books after making so much of an investment in them? Most sensible people would cut their losses earlier. Well, at least I can say I’ve begun to learn that lesson, because this time I only made it halfway through Atomised before I threw in the towel. My decision was most likely hastened by the fact that I caught a cold/flu (there were aching bones involved) and so my attention span for such a desolate view of humanity was much diminished. I can understand on an intellectual level that Houellebecq is theorising contemporary social relations or lack thereof, as his title suggests. And he is very clever in conveying the sense of alienation felt by his characters through his writing style. The trouble is that he is also successful in alienating the reader. I simply could not care for someone who sought relationships with very young women, while speaking about women his own age in the most derogatory way. I appreciate that such characterisation is part of Houellebecq’s thesis, but, well, I just wasn’t up for it. Even as I lay in bed recovering from illness, I couldn’t conceive of such a bleak vision. I longed for something life affirming.

I remembered a collection of short non-fiction pieces written by Edmund White and illustrated by Hubert Sorin, that I had picked up in a bargain bin at Target. Sketches from Memory: People and Places in the Heart of our Paris was conceived and accomplished while Sorin was dying from AIDS in the apartment he shared with White in the Châtelet district in Paris. Perhaps it was the drawings I wanted to revisit, something my poor diminished attention span could cope with. But that can’t be entirely true, for I found myself studying them in great depth. They are brilliant and comic and the figures seem to move. There are wonderful portraits of well-known figures of Sorin and White’s acquaintance, such as a young Naomi Campbell and the courtier Azzedine Alaïa.

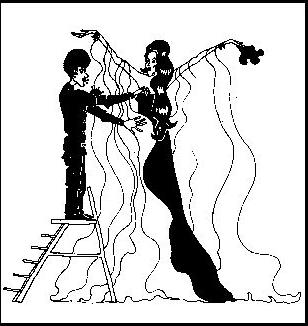

White writes:

White writes:I remember one night when the Galatea was a ravishing, pouting, smiling teenager, Naomi Campbell, who would later become the world’s most famous model but who then was just a sumptuously beautiful, shy English adolescent. She kept turning and turning as Azzedine ordered her to do, though when he stuck a pin in her she shouted lustily and tapped the tiny maestro on the head.

More important than the voyeuristic, though thoroughly charming, insights into the rich and famous, however, are Sorin and White’s portraits of the people who inhabit their neighbourhood, with whom they have affectionate, neighbourly relationships.

There are fishmongers, butchers, green grocers, buskers and building contractors; there are priests, prostitutes, eccentric homeless people and local dogs, all of whom are the friends of Sorin and White’s basset hound, Fred (after their friend Frédéric; they were unaware of the comic strip).

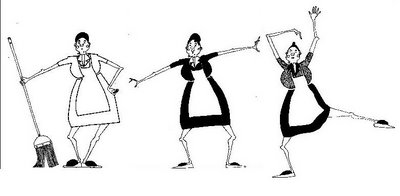

Madame Denise, the concierge of their apartment building, appears frequently. She is on the front line of demonstrators, protesting about several building projects in the neighbourhood; she is a despairing mother, trying to convince her son to marry; she likes to drink too much in the afternoon; and she is an incurious supporter of her gay charges, especially on the subject of Sorin’s illness. Most humorously, she is a willing model for the local hairdresser’s creative experimentation:

Madame Denise, the concierge of their apartment building, appears frequently. She is on the front line of demonstrators, protesting about several building projects in the neighbourhood; she is a despairing mother, trying to convince her son to marry; she likes to drink too much in the afternoon; and she is an incurious supporter of her gay charges, especially on the subject of Sorin’s illness. Most humorously, she is a willing model for the local hairdresser’s creative experimentation:

One day our concierge will look like a Roman matron, the next like a Neapolitan tart, then a week later she’ll become a Tonkinese princess or a cabaret singer of the 1940s, startlingly resembling the imposing, throaty lesbian chanteuse Suzy Solidor. Of course constant variety is the very source of the Parisienne’s power to bewitch us, but it’s somewhat disconcerting to see your motherly (and normally brunette) concierge coiffed with a bright red punk’s coxcomb at eight in the morning (or to be more honest—at ten).

While all of these portraits are tinged with the sadness that arises from knowing that Hubert Sorin is soon—within the time frame of the essays—to pass away, that Edmund White will be left alone after his lover’s death, the sketches are anything but bleak. This little book, remaindered no doubt to make way for ‘some vulgar, current best seller’, is finely wrought, and it made me laugh and cry. Reading it, I felt fully engaged with all the foibles of humanity.

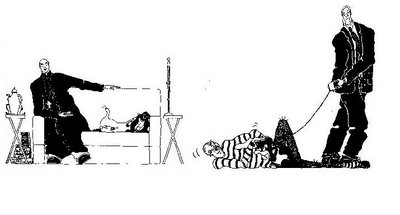

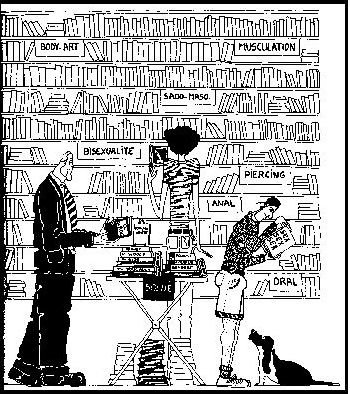

"In this drawing of our local gay and lesbian book shop, Les mots a la bouche, Hubert is daring to suggest that my books and other 'literary works' [the titles on the sale table include O. Wilde, V. Woolf, Proust, M. Foucault, A. Gide] of queer fiction are usually remaindered, whereas customers throng to the shelves selling pornography.

Update: Wendy at Sarsaparilla posted a great quote by Nabakov that addresses the conundrum I have recently faced in my reading. Look at this post by David as well. Glad I'm not alone in having a surfeit of half-read books littering my bedside.

No comments:

Post a Comment