If you’re interested in learning more about the programme and the history of cinema in Turkey and Iran, you can go and read the full text (pdf) that appeared in the free BIFF Catalogue. It seems superfluous to continue replicating it here, plus it diverts from my professed intention of offering a personal response to the films I’ve seen at the Festival. In total, I saw three feature length films and one short in this focus, and I watched them half aghast and half in admiration when I thought about the odds that the film-makers had to overcome, not only to get these stories to the screen, but also to ensure that prints of their films even continue to exist.

In an aside, I also went to a seminar this week about the documentation of the second wave feminist movement in Australia. As part of her presentation, Margaret Henderson recounted the dismal tone of Gisela Kaplan’s A Meagre Harvest, which laments the failure of the feminist movement in Australia as one that only yielded rewards for middle-class women and ‘a few film-makers and artists’. After seeing these films from Turkey and Iran, I couldn’t help but think that while human rights for all classes of women should continue to be a priority, we could probably afford to be a lot more optimistic about the ground made by those women who fought for all of our rights to represent ourselves.

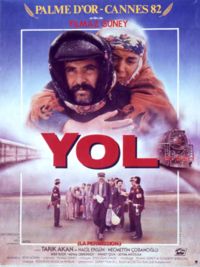

Yol

After I saw Yol (1982), by Turkish film-makers Yilmaz Güney and Serif Gören, I was a bit fragile. I ran into someone I knew, who asked me how I’d enjoyed it, and I had to blink rapidly, because as I began to talk about it I started to tear up.

Güney wrote Yol while he was in prison and Gören directed the film on his behalf. It tells the story of five men who are granted leave from their prison sentences for a week so they can visit their families. The film follows the prisoners on their journeys home to various parts of Turkey, and it is in this way that a mosaic of Turkish society emerges.

Güney wrote Yol while he was in prison and Gören directed the film on his behalf. It tells the story of five men who are granted leave from their prison sentences for a week so they can visit their families. The film follows the prisoners on their journeys home to various parts of Turkey, and it is in this way that a mosaic of Turkish society emerges.The men travel by bus and train and are all stopped at some point by the military demanding to see identification. One of the men has lost his ID, so he spends his leave detained, while the guards seek confirmation from the prison of his legitimacy. Others have their travelling delayed due to a curfew imposed by the military. Again, these men are detained, but at least only until the next morning.

The film shows a society where the military subject the Kurdish people to ongoing assault, and the Kurdish do not publicly admit to the identities of their dead for fear of further retribution; where a man is duty bound to marry his brother’s widow, and a widow has no choice but to accept her dead husband’s brother; where men freely visit prostitutes, and women are condemned to death for making a living in their husband’s absence.

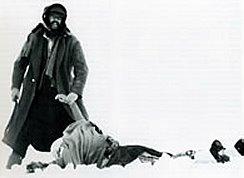

The most disturbing scenes of the film for me were those where one of the men travelled on a horse through the snow to retrieve his wife who had been locked up by her family for eight months, fed only bread and water, and denied any bathing facilities. The man’s brothers-in-law had been waiting for him to return home so he could have the first opportunity to restore their family’s honour, which had apparently been damaged by their sister when she prostituted herself. While the prisoner is angry at his wife’s infidelity, he is reluctant to kill her because he loves her. He has no choice but to make the journey through the snow—again, it is a matter of honour, his brothers-in-law will kill their sister anyway, but will condemn her husband if he doesn’t assert his authority.

There is no happy ending. The horse doesn’t make it, and on the journey back, its carcass has been scavenged by birds of prey and wolves. The wife begs that her fate not be the same as she too struggles against the snow, trailing after her husband and son, ill-dressed for the weather. Belatedly, the man tries the same method to restore his wife against the freezing conditions that he used on the horse, flogging her, to no avail.

There is no happy ending. The horse doesn’t make it, and on the journey back, its carcass has been scavenged by birds of prey and wolves. The wife begs that her fate not be the same as she too struggles against the snow, trailing after her husband and son, ill-dressed for the weather. Belatedly, the man tries the same method to restore his wife against the freezing conditions that he used on the horse, flogging her, to no avail.

No comments:

Post a Comment